In de afgelopen weken reisde onderzoeker Remco Raben door delen van Oost-Java om plaatselijke getuigenissen te verzamelen over de periode van de Indonesische revolutie. In onderstaande (Engelstalige) blog doet hij verslag van zijn ervaringen.

The hyper-local Indonesian revolution

Stories and sensations from around Bojonegoro and Mojokerto

by Remco Raben

Over the past weeks, I travelled through parts of East Java, in an explorative search for local voices from the revolutionary period of Indonesia. I want to share some of the experiences here, not because they were so successful or because they led to particularly original insights, but because they may tell something about the difficulties and possibilities of writing history from Indonesian perspectives in a history that can easily be weighed down by an overflow of Dutch archival material. My apologies to the impatient for the long post.

Preparing a publication on the administrative and political contexts of the violence in the Indonesian revolution, the evident but urgent question arises how to foreground the local experience, to present Indonesian voices and to give due attention to the victims. If one starts out on a traditional Dutch historical approach, by visiting archives, it is easy to find material on higher Dutch government and military levels. The overrepresentation of these voices leads to skewed histories.

Ironically, many Indonesian colleagues, when asked about the whereabouts of local Indonesian archives, suggested to look in the Dutch archives. When asked about newspapers, many referred to the digital repository of Dutch-language newspapers. Of course, there are useful stories to be found in Dutch collections. But those are brought together because of their relevance to Dutch authorities, and they never foreground Indonesian personal or governmental or archival concerns. They form no consistent and continuing storyline. It is of great importance to put as much effort as possible in retrieving the Indonesian voice. Oral history can bring us a long way – see f.i. Anton Lucas’s majestic One soul one struggle (1989) – but its possibilities are limited as time gobbles up the older generations.

The history of local government and the lower Indonesian officials is blurred and largely undocumented. There are scraps of (Dutch) reports of events at the very local level, and incidentally a few letters from Indonesian officials. There are also the Indonesian papers confiscated by the conquering Dutch troops, which now rest in the collection of the Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS) in The Hague. The National Archives in Jakarta of course hold some archives from ministries of the Republic in Yogyakarta. But evidence about specific localities remains sketchy and the details of local dynamics are difficult to retrieve.

Instead of going to see more archives, I decided to leave them for what they are and take a deep dip into local histories. The aim of the trip was to explore the possibilities of mobilizing local sources for writing the – Indonesian – administrative history of the revolution at a hyper-local level. Information could consist of anything: local (village) archives, eyewitness accounts, local oral traditions, local histories, and public history.

This was meant to be a reconnaissance trip, to explore possibilities for real research. Among the chosen spots were two areas in East Java, both reoccupied by the Dutch in the course of the revolution and both with a history of Dutch violence. One was Bojonegoro, 70 km west from Surabaya, on which the second Dutch offensive descended in December 1948, plunging the region in an extended period of violence and administrative confusion. The other was Mojokerto, southeast of Surabaya, already occupied by March 1947 and turned into a proeftuin, an experiment, famously failed, of a joint Dutch-Republican administration. But I was not after that story. I was interested in the local dynamics of administration and violence, and especially the attitude of Indonesian officials in the face of the Dutch occupation. How were villages and towns administered? How did the Dutch conquest impact on local relations? What was the leverage of local officials to counter Dutch violence?

Questions, questions.

What kind of knowledge did this exploration produce? It did not recover the local archives that once must have been there, but are now displaced, lost, or whatever happened to them. Probably trying to find them was a naïve aim, but it had to be done to ascertain their absence. It remains a dark mystery how ALL of the village and kabupaten archives have disappeared, in ALL the places I visited. The question lingers: what happened to them? Are they confiscated by the military, or have they all fallen victim to fire and neglect? Nationwide eradication seems improbable. But what then? Whatever the case, hardly a scrap of paper has emerged during the search for the local archives. In that sense, my exploration certainly had a clear result – a negative one.

Fortunately, much good history work has been done by regional historians and journalists. Using oral history, army reports, and newspapers, they often provide crucial information about main military events during the revolution. But they hardly tell us the story about how areas, towns and villages were administered, how village heads reacted to Dutch attempts to restore the colonial order, how loyalty issues split communities, how Dutch and Republican violence hit the villages, or how farmers reacted to pressures from fighter groups.

To get information, it is necessary to talk to the people. There are still octogenarians and nonagenarians who can tell stories on events befalling their villages in the late 1940s. I met many people who could provide detailed information on events. Besides those, there is much local tradition on the era, sometimes with astounding detail, especially of the deeply disturbing period of Dutch attacks and patrols and their aftermath. Names of victims, precise knowledge about locations of violence, accounts of horror and survival, they can all be found in the mnemonic sedimentation of the local community.

In one case, I had read some documents in the Dutch archives about Dutch military violence in villages to the southwest of Mojokerto, not far from the demarcation line between Dutch-held and Republican areas. There is a letter by the assistant-wedana of Trowulan, complaining to the Dutch authorities about Dutch soldiers killing civilians. In June 1949, a Dutch patrol discovered a bomb near the railtrack near Bojonegoro, which had failed to detonate. The Dutch soldiers brought the bomb into a nearby village and let it explode. They searched the village and killed several people.

I decided to look into local memories of the event. After calling in to the village head of Balongwono and asking around, my fellow researcher Ayuhanafiq and I came to speak to this wonderful man Pak Sukardji, who not only could confirm the story from the assistant-wedana, but could exactly tell the story of the Dutch action of revenge from the perspective of the villagers. The bomb was brought into the centre of the village and made to explode, next to a house of a rich man. The house seems to have been indicated by an informant helper (called ‘mata-mata’, spy, by the villagers). At least three farmers were killed by the Dutch patrol, one, Pak Giso, while cutting bamboo. Another, Pak Turah, was forced to climb a coconut palm and shot down. This all confirmed the reports in archives. And they constituted only one installment of the killing party. In other hamlets, the Dutch soldiers made more victims. The Dutch have not been called to account, but the dead are still sadly remembered in the villages.

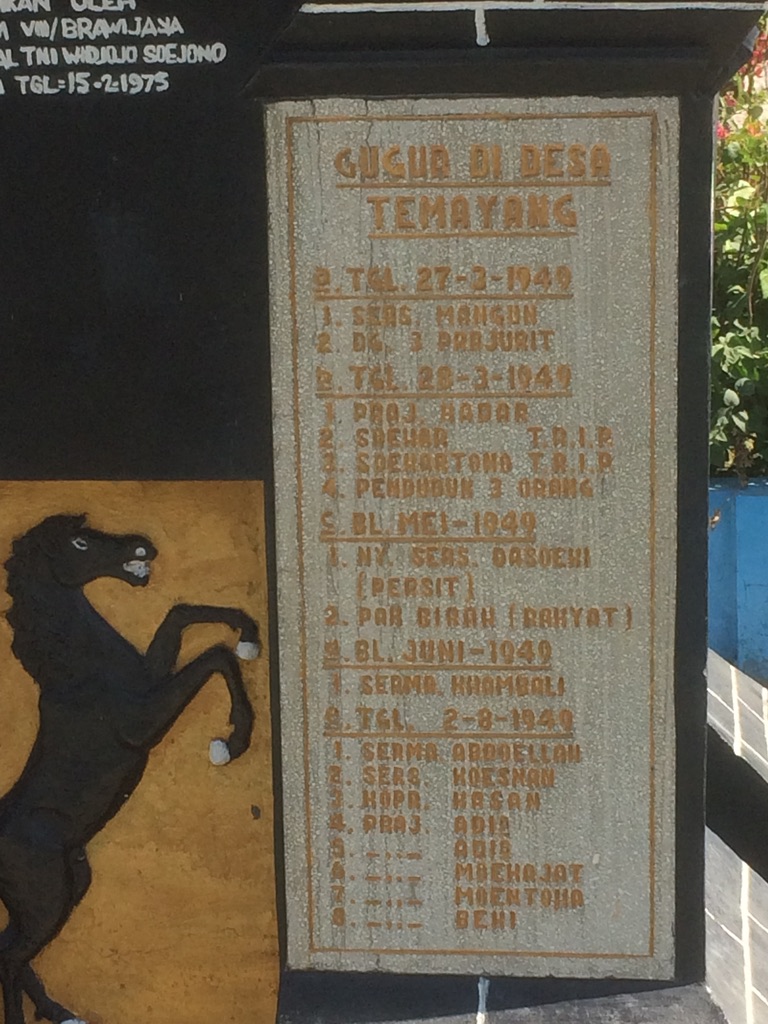

Memories are sometimes cast in stone. In a village to the far south of Bojonegoro, I stumbled upon a monument listing the tragedies of this small place. (See picture.) The village Temayang was a point of convergence of TNI troops and civil servants who had fled the Dutch occupation of Bojonegoro in December 1948. The famous Ronggolawe battalion of Basuki Rakhmat had taken refuge in the surrounding woods. This attracted Dutch patrols, who searched for the Republican troops and their helpers in the villages. After asking around, a village official brought me into contact with Pak Taslim, who told in great detail about the period. He remembered the Dutch forces recurrently coming to the village, always from the west – the road from Bojonegoro. On their arrival, Republican troops and villagers took flight to the woods, fields and hamlets surrounding the village. One day in March 1949, a Republican sergeant, Mangun, was caught while operating his mortar, and was immediately killed. The Dutch troops remained for three days in the village, hunting for Indonesian troops. The second day, three villagers who had given shelter to Republican soldiers were caught and executed by Dutch troops – their names appear on the village monument. Eventually the Dutch left and the people returned. Temayang also served as the backdrop of a meeting of the itinerant Republican governor of East Java with officials from Bojonegoro, who had fled the city and tried to establish a shadow government in the area.

Most village heads seem to have refused to work with the Dutch and fled with the people at the first rumours of Dutch approaching – although there were also exceptions. Fear for the Dutch ran deep. In one village, Sembung, closer to Bojonegoro, TNI fighters also patrolled the neighbourhood. Pak Achwan, the son of the wartime village head Ali Afandi of Sembung, told the story as his father had recounted. Attracted by the TNI activity, Dutch troops regularly descended on the village. On at least one occasion, the Dutch patrols used a fighter to bomb the supposed hiding place of Republican soldiers. The local story goes that helpers signaled to Dutch airplanes with mirrors to indicate the location of Indonesian troops. The strafing resulted in various casualties but no deaths. Rice sheds were burned down by revengeful Dutch soldiers. This, and the recurrent patrols, instilled a great fear among the farmers, who fled the village every time Dutch troops approached. A former kepala desa spoke of ‘traumatizing’ experiences of the village people.

A recurrent story line involves the use of local spies. The Dutch succeeded in mobilizing people to provide information. Purportedly this involved remunerations. Even the villagers of today acknowledged that opportunism and material gain was probably the main motive of the mata-mata. Not seldom, the informants were the target of revenge by guerillas or TNI soldiers. In Temayang, for instance, two informants, Pak Parto and Pak Sadiman, were killed by TNI in retaliation of their assistance to the Dutch.

All this is very enlightening. But perhaps the greatest value of this kind of historical fieldwork is not in the reconstruction of events. There is something unfathomably crucial to walk in the landscape of history. The experience of place, of the landscape, of distances, of the layout of villages, of the location of railway tracks and army posts, this all provides a kind of sensory knowledge that is essential to the historical imagination. Moreover, the discovery of village graveyards and monuments show how history endures. But above all, the opportunity to talk to the village people from all generations and walks of life produces an awareness of how history impacts on individuals and on communities. This perception cannot be obtained from the reams of bureaucratic paperwork to be found in the colonial archives.

As it happens, the history of the revolution and of the Dutch attempts at conquest is very much alive. Younger people know the stories from the village elders. Events that may be small in the big hubbub of revolution and war are the big stories of these places which, surprisingly perhaps, still retain a sense of cohesion and collective memory. The Dutch bombs, patrols, the recurrent violence, the fears, the internal splits, this all makes up a basic part of local history, largely orally transmitted, but sometimes eternalized in a modest monument.

One very last thing: everybody in the villages saw the Dutch attacks as an impingement on Indonesian independence. Dutch forces were seen as foreign occupiers, threatening the normal order and the livelihood of the village. In these areas around Bojonegoro and Mojokerto, as in most other areas on Java and Sumatra, the Republic started in 1945, and many if not most officials saw the events after the Dutch conquests of 1947 and 1948 as a violent intrusion on their affairs. The Dutch conquest, especially after the second great offensive of December 1948, seems to have created havoc and fear in the country. This is not a ‘spiral of violence’, as some have suggested, but a situation caused by failed Dutch military strategies.

With deep gratitude to Ayuhanafiq, Sita Nur Aulia, Lukiyati Ningsih, Pinilih Nugrahani, Purnawan Basundoro, Sarkawi Husain, the many kepala desa, village informants and, above all, the kind and generous interviewees for their help, hospitality, and stories.